Tuesday, July 11, 2006

Coffee - Commodity Profile - DA

The Philippines was once a reliable source of good quality Robusta from the late 1970’s to the early 1990’s (NCDB).The Philippines’ consumption from 1993-1995 was 48,000 tons. It has already reached 55,000 MT in 2004. While instant coffee is still the general preference, the ground and brew sector is growing. Organic coffee is the other growth area that the industry can look forward to.

Description

• The country has two most popular varieties of coffee: Coffea arabica, otherwise known as arabica, and Coffea canephora, or robusta.

• Based on statistics from the International Coffee Organization, robusta accounts for 75% of the country’s total production and Arabica, 5-10%.

• Other varieties such as excelsa and liberica, also, thrive in the country and accounts for 15-20% of the country’s coffee produce.

Production

• World coffee production in 2004 is 6.81 M mt or 113,479,000 60-kg bags up by 9.75% from 2003 but is still much lower than the production in 2002 of 7.32 M mt, the highest production in decades.

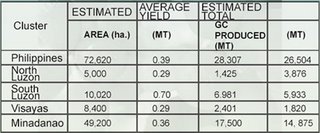

• The top producing countries in 2004 are Brazil (2.3 M mt of Arabica), Vietnam (0.90 M mt of Robusta), Colombia (0.63 M mt of Arabica) and Indonesia (0.34 M mt of Robusta)• Based on the data of Nestle the total productive coffee area in the country is about 72,620 hectares with 49,200 hectares in Mindanao.

• The average yield is only 0.39 mt/ha but the potential is 2-3 mt/ha given the right management.

• It is estimated that around 300,000 Filipinos depend on the coffee industry.

Estimated Production, 2003-04 (Nestle)

(See table from the website)

Processing

• Aside from the instant coffee players such as Nestle, URC and San Miguel there are other players in the market such as Kopiko and Kape Filipino,

• In the ‘Ground and Brew’ the signi. cant players in the local market are Figaro, Monk’s Blend, Café Amadeo, Batangas Brew

• Available also in wet markets are roasted beans of robusta and liberica for grinding

Cost and Return

• In Cavite total cost of production is P27,461.50/ha if with fertilization on a yield of 1000 kg/ha and P15,000.00/ha if without fertilization on a yield of 400 kg/ha green bean

• In Sultan Kudarat the cost of production for Robusta is around P27/kg as monocrop and P23/kg with intercrops.

• Net income is P20-30,000/ha at P43/kg green bean

Demand and Supply Projections

• Domestic demand stands at 55,000 MT

• Domestic production is around 27,000 MT in 2004

• The shortfall of 30,000 MT is imported at a total of US$ 25 M/yr

• Local demand is growing at 3%/year to about 65,693 tons by 2010 and 78,439 tons by 2015

• The country will be importing 46, 000 tons by 2010 at the present rate

• In terms of expansion area for coffee Mindanao has enough area to answer for about 70% of the projected 10,000-hectare per year expansion needed to be self suf. cient

• There is also an increasing local demand for organically grown coffee and other specialty coffee such as Phil. Barako Coffee, Halal Coffe, Phil. Excelsa Coffee and Kape Alamid

Local Market

• Nestle has about 80% of the market

Foreign Market/Trade

• Top exporting countries in 2004 are Brazil (1.58 M mt), Vietnam (0.89 M mt), Colombia (0.61 M mt) and Indonesia (0.27 M mt)

• The Philippines exported $4.51 M worth of coffee products. Liberica and Excelsa accounted for $0.14 M

• In 2004 the Philippines imported 15,087 mt of raw green beans, roasted beans and extracts worth USD 25.49 M

• Robusta green bean import in 2004 was 8,196.4 mt at $ 7.63 M or $0.93/kg• Arabica green bean import in 2004 was 81.34 mt at $1.144/kg

Marketing Practices

• Farmers generally dry their coffee beans and have them milled through local millers.

• Green beans are sold to traders or directly to the buying stations of Nestle or to wet markets

Problems

• low production,

• low income of coffee farmers,

• poor quality of coffee beans,

• lack of postharvest facilities for quality processing,

• highly . uctuating market prices

Price Trend

• Prices of Robusta is highly volatile- P43/kg in March 2005 and P70/kg in July 2005

• Arabica is higher at up to P110/kg

Credit Assistance

• Quedancor- Self-reliant Team (SRT), P28,000/ha for rehabilitation maximum of P50,000/farmer

• Land Bank of the Philippines- P45,000/ha for rejuvenation, P60/ha for new plantings

Investment Opportunities

• Credit facilities for rehabilitation- P300 M• Nurseries for seedlings of Robusta, Arabica and Liberica

• Coffee plantations for robusta, Arabica and liberica• Post harvest facilities • Processing for the ground and brew

Institutional Support

• A priority commodity under HVCC

• National Coffee Development Board

• Cavite State University

• Benguet State University

http://www.da.gov.ph/mindanao/com_profile/coffee.html

Coffee Breakthroughs down south - Nestlé’s new farming methods produce high-quality coffee

By Dennis Ladaw

COUNTLESS classy, trendy cafés have been sprouting all over Metro Manila, much to the delight of the caffeine-addicted citizens of this metropolis. Many of them go on a drinking binge, which begins in the morning, and ends in the wee hours of the morning.

Coffee cherries Proprietors of bars that serve liquor could only wish they had the kind of clientele that Starbucks and the like cater to.

According to Nestlé Philippines, producer of the venerable Nescafe brand of coffee, it was in the sixties when the Philippines emerged as Asia’s top coffee exporter. This continued on up to the eighties.

However, by 1995, the country became a net importer of coffee. Local coffee production declined as aggressive Asian countries like Vietnam boosted their own coffee production. And this came at a time when our Filipino farmers have been having difficulty producing top quality coffee, as they remain incognizant of superior farming methods. With inconsistent yields, life became difficult for local farmers.

To counter this effect, Nestlé embarked on a major program to introduce new methods of coffee farming to local farmers. Through the Nestlé Experimental and Development Farm (NEDF), the program is also promoting a new system that encourages farmers to convert their plantations into multicrop-producing lands.

NEDF occupies a sprawling Nestlé property in Tagum City, an hour’s drive from Davao City. The place had once served as a technical training facility for the company. But now it’s open to farmers who want to boost their yields and increase their income. The course is given for free, according to NEDF’s resident agronomist Cenon Alenton.

Alenton also serves as a trainer, and he notes that most of the country’s coffee farmers have had no formal training. “By introducing the farmers to more effective agricultural methods and new technology, they can drastically increase the quality and quantity of their harvest. We really need to encourage coffee farming, and that begins with getting the proper training,” he said.NEDF also encourages farmers to engage in organic farming and plant other crops to help them sustain their livelihood while waiting for the coffee crops. Alenton said legumes, root crops, vegetables and other fruit trees could be intercropped with coffee. Recommended legumes are peanuts, mongo beans, string beans and white beans. For root crops, Alenton listed gabi, sweet potato or ube.

The three could be planted in between the coffee plants, he said.

Joel Lumagbas, Nestle’s vice president for agricultural services, said the choice of the companion crop should be profit-driven. “A farmer could further increase his profits by choosing a high-income companion crop called the Jatropha curcas, a bio-fuel oil crop. It’s ideal because one planting will last up to 50 years. It’s used as fuel for lighting, cooking and soap making,” he pointed out.

Meanwhile, Alenton said good harvesting methods and processing contribute much to the ideal taste of coffee. NEDF advocates the manual harvesting of coffee or the physical removal of ripe berries from the trees, as this method allows the selective removal of yellow and red ripe berries from the cluster. The green or immature berries are left behind for future harvest to avoid producing low-quality coffee beans. “Green berries yield flat beans, which burn fast in roasting, producing a bitter taste,” he explained.

Alenton and Lumagbas played host to a group of media reporters, who toured the NEDF. His fellow trainers even conducted an Amazing Race of sorts, with the media practitioners divided into three teams. The race aimed to pick out the highest quality beans from the NEDF plantation and sort out the best quality beans. The game helped us realize the complex procedures of producing quality coffee (as we realized how some media people could be so obsessed with winning a race!).

NEDF was established in 1994 and it has since trained over 10,000 farmers and agricultural students, which is equivalent to one-fifth of the country’s total coffee farmers. Alenton said that the new procedures they’ve been introducing will also help farmers sell their yields at a profitable price.

The efforts of NEDF seem to paying off. Joel Lumagbas said that in recent years harvesting and processing have “generally improved” with many coffee farmers now delivering grade 1 or grade 2 coffee beans.

Although our brief visit to the NEDF may not have turned us into expert farmers, many of us did turn into coffee connoisseurs to be feared by all cafés who buy cheap green berries.

http://www.manilatimes.net/national/2006/mar/18/yehey/life/20060318lif1.html

FAO Coffee Projections

Coffee

Introduction

A dynamic model was used to make coffee projections. It covers the major exporting and importing countries of green coffee. Supply, demand and stock functions were estimated for each of the major exporting and importing countries. The model performs dynamic simulation forward in time and generates forecasts on the basis of assumptions for the future behaviour of GDP, consumer price indices and exchange rates. For each year in the future, the International Coffee Organization’s composite price is solved in order to achieve equilibrium between supply and demand for green coffee. This model was developed to provide forecasts for green coffee production, consumption and trade, assuming that coffee is treated as a homogeneous commodity with no distinction between Arabica and Robusta varieties.

Production

World coffee production is projected to grow by 0.5 percent annually from 1998 - 2000 to 2010, compared to 1.9 percent of the previous decade. Global output is expected to reach 7.0 million tonnes (117 million bags) by 2010 compared to 6.7 million tonnes (111 million bags) in 1998 - 2000.

The world's largest coffee producing region is likely to continue to be Latin America and the Caribbean, although the projected annual growth rate for the region is expected to decrease from 1.7 percent in the previous decade to 0.4 percent annually during the projection period. Its output is projected at 4.0 million tonnes (67 million bags) by 2010, compared to 4.2 million tonnes (70 million bags) in 1998 - 2000. Coffee production in Brazil in 2010 is expected to decrease to 1.3 million tonnes (22 million bags), compared to 2.1 million tonnes (35 million bags) in 1998 - 2000. In Brazil, improved prices from the mid - 1990s stimulated planting and replanting after a period of decline when growers responded to lower prices by reducing the use of agricultural inputs and uprooting plants in marginal areas. In Colombia, based on the age profile of the coffee areas, output is projected to grow at an annual rate of 0.7 percent to 2010 to reach 747 000 tonnes (13 million bags), compared to 699 000 tonnes (12 million bags) in 1998 - 2000. Some plantings took place during the 1990s in response to the surge in demand for Colombian Milds, which fetch premium prices over other Arabicas.

In Central America, output in Mexico in 2010 is expected to reach 273 000 tonnes (5 million bags), more or less the same as the base period. In Guatemala, the projected annual growth rate of 1.7 percent would take production to 348 000 tonnes (6 million bags) by 2010. A growth rate of 3.9 percent for El Salvador is likely to bring their output to 165 000 tonnes (3 million bags) by 2010, while Costa Rica should experience an increase of 4.2 percent that brings output to 194 000 tonnes (3 million bags).

In Africa, coffee production is expected to increase by 1.5 percent annually from the base period to 2010, mostly reflecting increases in yields rather than an expansion in area. Output is anticipated to increase from 961 000 tonnes (16 million bags) in 1998 - 2000 to 1.1 million tonnes (19 million bags) by the year 2010. Production in Ethiopia, the largest Arabica coffee producing country in Africa, is expected to expand by 1.6 percent annually to reach 207 000 tonnes (3 million bags) by 2010. Coffee output in Côte d'Ivoire is expected to increase by 3.8 percent per annum, which would likely bring its output to 217 000 tonnes (3.6 million bags) by 2010.

The output in Uganda is projected to increase at a rate of 0.7 percent annually from 1998 - 2000 to 2010. Output may rise to 222 000 tonnes (4 million bags) by 2010 from 207 000 tonnes (3 million bags) in 1998 - 2000, through replanting and higher yields. Kenya, the African producer of Colombian Milds, is projected to expand output by 1.1 percent annually during the projection period to arrive at 88 000 tonnes (1.5 million bags).

Production in Asia is projected to grow by 2.1 percent annually to reach 1.7 million tonnes (29 million bags) by 2010. Much of the expansion is expected to occur in Indonesia, the largest producing country in the region. Its coffee production expanded rapidly during the 1970s, slowed in the 1990s and is projected to expand at a growth rate of 1.7 percent annually to 2010 when output is likely to reach 654 000 tonnes (11 million bags). Also, in India output is projected to rise at 3.1 percent annually to reach 409 000 tonnes (7 million bags) by 2010. An increase of 2.0 percent per annum is expected in Viet Nam, where output could reach 561 000 tonnes (9 million bags) by 2010. An annual increase of 0.7 percent is expected for Thailand, where output is projected to reach 59 000 tonnes (1 million bags) by 2010.

In Oceania, Papua New Guinea is the only significant producing country. Its production has been relatively stable during the 1980s and its output in 2010 is estimated at 150 000 tonnes (3 million bags).

Consumption

World consumption of coffee is projected to increase by 0.4 percent annually from 6.7 million tonnes (111 million bags) in 1998 - 2000 to 6.9 million tonnes (117 million bags) in 2010.

Coffee consumption in developing countries is projected to grow from 1.7 million tonnes (29 million bags) in 1998 - 2000 to 1.9 million tonnes (32 million bags) in 2010, at an annual rate of 1.3 percent, while their share in the world market is expected to increase from 26 percent in the base period to 28 percent in 2010. The projected higher growth rate for developing countries compared to developed countries is due mainly to higher income and population growth in developing countries, with increased coffee consumption continuing to be concentrated in the major coffee producing countries.

Developed countries, including countries in transition, are likely to continue to account for the larger, though slightly declining, share of world coffee consumption. In the base period their share of consumption was 74 percent, nearly 5 million tonnes (83 million bags), compared with 72 percent projected for 2010. Coffee consumption in developed countries is projected to grow by 0.1 percent annually to 5.0 million tonnes (83 million bags) by 2010. In Europe, demand for coffee is projected to increase by 0.4 percent per year to 3.1 million tonnes (51 million bags) by 2010. The European Community (EC) is projected to account for 2.2 million tonnes (36 million bags), or 68 percent of total consumption in Europe. Demand is expected to rise slightly in the EC, but growth in consumption in the rest of Europe, excluding the former Soviet Union/CIS, is expected to show a slight decline. Growth in the former Soviet Union/CIS is expected to be more or less the same as in the base period. In North America demand is projected to decrease by 1.0 percent per year, mainly reflecting income and population growth in the region.

Trade

In 2010, global coffee net-exports is projected to reach 5.5 million tonnes (92 million bags). Latin America and the Caribbean, with an export of 2.9 million tonnes (48 million bags), is expected to continue to be the leading exporting region, although there will be a decline in the net-exports of 0.5 percent annually. By contrast, in Africa there will be a net export increase at a rate of 1.6 percent annually, reaching 1.0 million tonnes (17 million bags) and accounting for a 18 percent share of global exports. In Asia, export availabilities are expected to grow to 1.5 million tonnes (24 million bags) in 2010, accounting for 27 percent of world coffee exports. Export availabilities from Oceania are estimated to increase by 7.3 percent, reaching 150 000 tonnes (2.5 million bags), about 3.0 percent of global export availabilities.

World coffee imports are expected to increase by 0.2 percent annually during the projection period to reach 5.5 million tonnes (92 million bags) by 2010. This compares with average imports of 5.4 million tonnes (90 million bags) in 1998 - 2000. Imports by developing countries are projected to reach 421 000 tonnes (7 million bags) in 2010, accounting for less than 8 percent of the world's total and similar to their share in 1998 - 2000. Reflecting the slower growth of consumption, import requirements of the developed countries are projected to grow at an annual rate of 0.1 percent, reaching 5.1 million tonnes (85 million bags) by 2010 and accounting for 92 percent of the global total. Import demand by North America is projected to decline moderately to 1.54 million tonnes (26 million bags) by 2010. Imports into Europe are projected to decrease marginally to 2.96 million tonnes (49 million bags) by 2010. Imports to Japan are projected to grow at 1.6 percent annually reaching 460 000 tonnes (7.7 million bags).

Growth in import demand by the former Soviet Union/CIS, where consumption in soluble form has grown but no processing firm has been established in the area, is expected to remain low at less than one percent per annum during the projection period.

Issues and uncertainties

The result of the projections indicates that global green coffee demand and supply would continue to grow, although at a rate slower than in the previous decade, and be almost in balance at around 7 million tonnes by 2010. The projections indicate that several major changes would take place in the world coffee market to 2010. First, most production growth would come from Asia and Africa, instead of Latin America where most coffee had been produced. Second, the growth of consumption would be faster in developing countries than in developed countries, in contrast to the trend over the previous decade. Part of the growth in consumption in developing countries would come from the increase within the producing countries, and partially because of this, international trade would grow slower. This scenario, however, is subject to sudden and substantial changes in the world coffee economy.

Recent price crises have had an important implication for the world coffee economy. The price crisis, which has adversely and seriously affected incomes of all coffee producers, hit some producers more severely than others due to differences in various economic factors such as production cost and exchange rates. These variations may change the relative competitiveness among the exporters, and could therefore alter the pattern of the world coffee trade. In addition, various international initiatives are expected to take place as the exporters underline the importance of promoting higher quality coffee with the aim of improving prices through boosting consumption. All these factors may affect the demand and supply conditions in the world coffee markets to 2010 although the price would continue to be the primary determinant.

Table 2.26.

Coffee: actual and projected production

To see table go to this website :

http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y5143e/y5143e0v.htm

World Coffee Production Forecast

Go to this website :

http://www.fas.usda.gov/htp/tropical/2005/12-05/December%20All%20PDF.pdf

The journey of a coffee bea

NESCAFÉ Classic has been a part of Philippine culture so much so that when one mentions coffee, it is the brand that immediately comes to mind.

However familiar we are with its taste and aroma, not many of us know the strict and rigorous process that coffee beans used in Nescafé Classic undergo.

From the planting and propagation of the Robusta coffee cherries to their careful selection by coffee farmers and the special roasting process that they undergo, coming up with a rich and flavorful cup demands a lot of hard work and quality control.

The first step to quality coffee is good farming. And with the Nestle Experimental and Development Farm in Tagum, Davao del Norte, coffee farmers are trained with modern farming systems and are given access to high quality and high-yielding Robusta coffee planting materials.

To date, the NEDF provides 80 percent of all Robusta cuttings used in the Philippines.

“A coffee is a 50-year crop,” says Zenon Alenton, resident agronomist for NEDF. “If you plant a bad coffee tree, it means harvesting 48 years of bad coffee.”

The next step involves the practice of good harvesting methods. This involves the physical removal of the coffee cherries from the trees, one of the most important stages in coffee production as it, along with roasting, contributes to good coffee taste and aroma.

“It is best that the cherries be carefully handpicked by the farmer because this allows the selective removal of ripe cherries from the cluster,” explains Alenton. “Harvesting green berries with red ones will result in immature beans after processing. Green cherries yield flat beans, which burn fast in roasting, thus producing a bitter taste. Overripe cherries, meanwhile, produce an acidic taste.”

Alenton says red coffee cherries are more fragrant and smooth because of its higher aromatic oil and lower organic acid content.

The coffee cherries then undergo a post-harvest treatment. Here, they are poured into a floatation tank to help separate the floaters from sinkers. Floaters are insect-damaged or unfilled cherries, while sinkers are good quality ripe cherries that are free from insect damage.

The coffee cherry sinkers then go through drying and sorting.

“Drying is necessary to prevent microorganisms from growing during storage,” explains Alenton. “The coffee cherries can be dried in the sun or in mechanical driers.”

The coffee cherries are then sorted. “This involves the selection or taking out of undesirable foreign materials or broken pieces of coffee beans that can degrade or bring down their quality,” says Alenton.

After sorting, the beans are delivered to the Nescafé buying stations. Currently there are 11 coffee buying stations nationwide by Nestlé Philippines Inc. Here, they are graded according to moisture content, percentage triage, and cup taste. “Coffee with moldy, fermented and or foreign taste is immediately rejected,” says Alenton.

The chosen coffee cherries are then stored, where equilibrium between the water inside the bean and the humidity of the ambient air is maintained.

The final and most integral part in the processing of the Nescafé Classic is the roasting.

“Nescafé has mastered the art of roasting to perfection. Its special roasting process brings out the fresh, flavorful taste and rich aroma of the coffee cherries. And this is the reason why its rich taste and aroma is very distinguishable from other coffee brands,” says Alenton.

During the roasting process, the coffee cherries expand and undergo density and color changes.

They turn to yellow once they absorb heat and then to brown as the beans in the cherries are pushed out. They further darken in color once they release the oils, which give coffee its flavor.

These are the stages that the Robusta coffee cherries used in the Nescafé Classic undergo and these are the processes that make it the most popular coffee choice in the country.

http://www.manilastandardonline.com/iserver?page=goodLife03_july05_2006

A bitter brew for coffee farmers

The Toronto Star: Aug. 4, 2002

Growers struggle even as sales soar for gourmet beans

Oakland Ross, Feature Writer

Maria Fiallos is not your average Nicaraguan coffee grower.

For one thing, she's making money, at a time when most Nicaraguan coffee growers — like most coffee growers all over the world — are losing their tattered and sweat-stained shirts.

For another thing, she doesn't live in Nicaragua. She lives in London, Ont., where she manages a small family-owned coffee-importing business called Aroma Nica.

Her father, Reynaldo, takes care of the tropical end of the operation, tending to the needs of a small but lofty coffee finca that hugs a cool Central American mountainside in the northwestern Nicaraguan province of Madriz, a property that has belonged to the Fiallos family for three generations.

Each year, the plantation yields about 17,200 kilograms of premium, high-mountain arabica coffee, all of which finds its way north to Canada.

This small Nicaraguan crop is, to the world of coffee, what fine, estate-bottled Burgundy is to the world of wine.

A stickler for quality, Reynaldo Fiallos raises his crop organically, in the cool, chiaroscuro shade of a rainforest canopy at more than 120 metres above sea level. The ripe beans are then picked by hand and gently conveyed to market.

Canadian coffee roasters and specialty outlets are willing to pay a premium to acquire such high-grade beans, eagerly shelling out three or four times the current base price for standard-grade coffee, as set by the New York Coffee, Sugar and Cocoa Exchange.

"Our prices for the past couple of years have remained pretty stable," Maria says. "We're quite lucky we're getting these kinds of prices."

Millions of mainly small-time coffee growers scattered across some 50 tropical countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa undoubtedly wish that they could say the same.

Instead, they are ready to scream.

"It's just a terrible situation," says Peter Pesce, owner of Reunion Island Coffee Ltd., a small Toronto coffee roasting operation. "You have this tremendous glut."

In fact, you have an unprecedented glut — far too many people in far too many places planting far too much coffee.

Consumption of the dark and jittery brew may well be on the rise in North America, Europe and Japan, but that trend has not kept pace with a pell-mell increase in supply.

The resulting imbalance has spelled abysmal prices and misery for millions of unfortunate people who devote themselves to growing the feisty little beans that kick-start millions of yawning, bleary-eyed souls at the dawn of each new day.

Five years ago, in May, 1997, the base rate for mild, standard-grade arabica beans on the New York coffee exchange was slightly more than $3 U.S. a pound. Today, that pound is fetching less than 50 cents.

Mostly cash-strapped to begin with, vast legions of coffee growers are now losing money, because you cannot produce a pound of decent coffee for spare change.

"It is a crisis," says Sandy McAlpine, head of the Coffee Association of Canada, an umbrella group representing Canadian buyers, roasters and sellers. "It's a classic imbalance of supply and demand."

To judge by the quantities of caffeine nowadays being imbibed with earnest abandon by Toronto café denizens, you might have thought that the demand side of the coffee biz was buzzing along just fine.

And so it is, if you happen to reside in wealthy northern climes, where specialty coffee shops delight their customers' palates — and make light of their wallets — with a mesmerizing variety of high-end coffees and coffee-based drinks.

Sales are up, and consumer prices are not exactly going down.

Coffee now ranks as Canada's single most popular beverage. In the United States, it is exceeded in popularity only by soft drinks.

Europeans and especially Scandinavians are devoted to coffee, too.

You'd think it would all add up to heart-quickening news for the coffee growers of the world.

But it isn't so.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

'A lot of growers can't afford to pick their crops and are laying off their workers'

Coffee importer Maria Fiallos

If you had the ill fortune to be a small-time coffee farmer in Nicaragua, say, or Mexico, or Kenya, then you might be cursing the day you first got the stupid idea of planting coffee trees on your little plot.

Worse, if you happened to be a landless peasant, employed by the day to pick coffee on someone else's property, you would probably be at your wit's end by now, forced to abandon the countryside and trudge with your children toward a city to beg for your keep, just as thousands of Nicaraguan peasants have lately been doing.

According to a recent report in La Prensa, the leading Nicaraguan newspaper, some 12,000 jobless and desperate people have congregated outside the northern city of Matagalpa — in the heart of the country's main coffee-growing region — after straggling down from the now-paralyzed coffee plantations in the surrounding hills.

"A lot of growers can't afford to pick their crops and are laying off their workers," says Fiallos. "Some cannot meet their obligations to the bank and are going bankrupt."

Who is to blame?

Some people point their stir-sticks at the specialty coffee chains, companies reaping handsome profits while legions of dirt-poor coffee growers and workers go under.

Just this week, for example, Starbucks Corp. — the world's largest chain of coffee houses — reported net revenues of $261 million, an increase of 26 per cent over the comparable period in 2001.

Others hold the true giants of the coffee world to account: the big conglomerates such as Proctor & Gamble and Philip Morris. They dominate global coffee sales, cramming supermarkets with vast amounts of not-especially-good coffee, while paying rock-bottom prices to producers.

Still others peer to the east, toward poor, benighted Vietnam, which recently vaulted from nowhere in the business to become the second largest coffee producer in the world, edging out Colombia. Only Brazil produces more.

Or maybe the World Bank is at fault, for having encouraged Vietnam to go into coffee-growing in a big way in the first place.

Or why not simply blame Mother Nature?

This year, Brazil has been blessed, or damned, by perfect coffee-growing weather, resulting in a bumper crop of beans. Result: still more coffee and still lower prices.

It would be bad enough if small growers were indeed able to earn a measly 50 cents U.S. a pound for their coffee. But, in fact, the situation is often even worse.

Typically, a parade of middlemen stands, hands outstretched, between the producer and the vacuum-sealed bag. As a result, a grower might receive 25 cents or even less per pound of green coffee.

"There is a fair bit of exploitation at the level of these middlemen," says Caroline Whitby, managing director of Transfair Canada, which markets high-quality coffee purchased at above-market prices. "The more isolated the community is, the more vulnerable the producers are."

Whitby's outfit is part of an international network of commodity marketers seeking to ensure that small-time growers get a just price, what's known as the Fair Trade movement.

At present, her organization pays $1.26 U.S. per pound of coffee, or roughly 2.5 times the current base price as set in New York. The money is distributed to growers' co-operatives in 22 countries. The co-ops deduct their expenses before passing the rest on to individual producers, who typically wind up with about 80 or 90 cents U.S. per pound of beans, still vastly more than they would probably receive otherwise.

"It's not about charity; it's about justice," says Laure Waridel, Canadian author of Coffee With Pleasure, a recently published book about the international coffee business.

At the outset of her research, done largely in Mexico, Waridel regarded Fair Trade as a naïve and unrealistic response to a complicated problem, "a feel-good thing," as she puts it.

Now she feels differently. "I realized how much of a difference Fair Trade can make," she says.

Not everyone agrees.

"In terms of market impact to date, Fair Trade is a very small presence," says McAlpine at the Coffee Association of Canada. "I'm not sure it's ultimately the solution."

In fact, Second Cup — like other specialty coffee outfits, including Starbucks — also pays prices well above the New York base rate, often after negotiating multi-year purchase agreements with suppliers.

The gourmet chains do this not out of unalloyed altruism, but because decent prices are the only way to ensure a reliable supply of superior beans over the long haul.

"We do know there is a premium, and we're prepared to pay it," says Alton McEwen, Second Cup's CEO. "You cannot produce really good coffee at a low price."

'We're not a part of the problem and we're not a part of the solution. We're so small. The big volumes are going through the supermarkets.'

Second Cup CEO Alton McEwen

Unfortunately, really good coffee — the kind that will set you back $10 to $14 for a pound of whole beans at a high-end Toronto store — is a fairly scarce commodity. It must be grown in cool, shady conditions, in rich soil, at high altitude — about 5,000 feet above sea level. It must be protected from pests and damage and be picked by hand.

"There's not that many places in the world that have an ideal climate at that altitude," Pesce says.

For the most part, the men and women who grow such coffee are not the people suffering now.

In fact, they represent a tiny part of the global coffee business, producing only about 5 per cent of the 6.03 billion kilograms consumed around the world in any given year.

"We're not a part of the problem and we're not a part of the solution," McEwen says. "We're so small. The big volumes are going through the supermarkets."

And the big volumes are mainly controlled by just four multinational companies: Proctor & Gamble Co., Philip Morris Cos. Inc. (through Kraft Foods), Nestle S.A., and Sara Lee Corp.

Together, they market dozens of brands, few of which approach the complex "flavour profile" of the blends or varietals on sale at specialty coffee houses.

The difference is mostly a matter of beans.

True, some supermarket coffee is composed entirely of arabica beans, albeit probably not the best arabica beans. But much of the coffee on the grocery store shelves contains a considerable portion of ground robusta beans, mixed with some arabica for the sake of flavour.

Highly resistant to disease and chock full of caffeine, robusta beans can be grown at low altitude and without shade, and are therefore inexpensive to produce. Alas, in the taste department, robusta coffee doesn't amount to a hill of, well, beans. Vietnam grows robusta beans almost exclusively.

"You can make a cheaper coffee by putting in more robusta," concedes Bruce Legge, Sara Lee's director of Canadian coffee sales.

Maybe so, but Canadian consumers have failed to reap savings at the supermarket, despite cheap beans.

This is partly a matter of packaging. The big marketers have responded to falling prices by putting their product in ever smaller containers, downsizing from 369-gram packages to, lately, 250-gram. Such tactics have helped hold prices up.

"The pricing has remained relatively flat over the past few years," says Legge, who argues that consumers have nonetheless been getting a break in some cases.

He points to big-box outfits such as Costco or Wal-Mart, which have spawned a new trend in coffee vending: economy-size packs of roasted-and-ground coffee tumbling off the shelves at low prices.

Unfortunately, anyone who buys an entire kilogram of ground coffee in a single container is probably making a mistake, even at $4.89 Canadian, because ground coffee pretty much turns to gravel about a week after purchase.

What, then, is the solution?

People such as Caroline Whitby at Transfair Canada urge coffee lovers to buy more Fair Trade beans — and it certainly wouldn't do any harm if they did.

Some 30 Toronto-area businesses sell Fair Trade coffee, at prices competitive with premium coffee generally. For a list, go to Transfair Canada's Web site at www.transfair.ca/index.shtml and follow the coffee link.

Many others involved in the coffee trade say that lasting solutions must either increase demand or reduce supply — or do both.

"Unfortunately, the solutions are very long-term," says McAlpine at the Coffee Association of Canada. "None of them will have much impact tomorrow."

On the demand side, he endorses ongoing efforts to promote coffee in China and Russia, two major potential markets still more enamoured of tea. He also suggests that people in coffee-growing countries should start drinking more of their own brew, something happening in Brazil, for example.

On the supply side, many people see just one painful way out: A lot of growers will simply have to bid the business adieu.

Marginal lands will have to be taken out of production, they say, making room for other crops.

The need for such restraint may be acute in one Southeast Asian land.

"The Vietnamese will have to cut back," McAlpine says.

A lot of people believe matters would improve if there were simply more good coffee on the market, as opposed to the dreary fare that tends to fill grocery shelves now.

"If you give somebody good coffee," says Pesce at Reunion Island, "they'll drink one or two cups, rather than leave half a cup."

It's a start.

http://arts.yorku.ca/sosc/buso/links/buso_bitter.html

Monday, July 10, 2006

Gov't to extend assistance to Mindanao coffee growers

GOVERNMENT financing institutions have earmarked credit assistance to coffee growers in Mindanao.

During the recent Mindanao Agri-Fisheries Investment Forum, the Department of Agriculture (DA) announced that Quedancor and the Land Bank of the Philippines is offering credit assistance per hectare to coffee growers in Mindanao.

Quedancor under the self-reliant team (SRT) offers P28,000 for hectare for rehabilitation and a maximum of P50,000 per farmer while the Land Bank of the Philippines extends P45,000 per hectare for rejuvenation and P60,000 for new planting.

The DA reported that the Philippines' consumption of coffee from 1993-1995 was 48,000 tons and reached 55,000 metric tons in 2OO4.

Instant coffee is still the general preference but there is a growing demand for the ground and brew sector with the organic coffee as the other growth area.

Of the total productive coffee area in the Philippines of 72,620 hectares more than half of the total figure or about 49,200 hectares are found in Mindanao.

With right management of area planted to coffee it could yield an average of two to three metric tons per hectare as against the current average yield of only 0.39 metric tons per hectare.

There are about 300,000 Filipinos that depend on the coffee industry.

In 2004, the Philippines imported 15,057 metric tons of raw green beans, roasted beans and extracts worth US $25.49 Million.

Robusta green bean import in 2004 was 8.197 MT at $7.63 million or $0.93 per kilogram while the Arabica green bean import last year accounted for 81.34 MT at $1.144 per kilogram.

Coffee is among the nine prioritized commodity in Mindanao.

The eight other commodities are rubber, coconut, poultry, banana, mango, palm oil, seaweeds, and tilapia.

For Bisaya stories from Davao. Click here.

(August 26, 2005 issue)

http://www.sunstar.com.ph/static/dav/2005/08/26/bus/

gov.t.to.extend.assistance.to.mindanao.coffee.growers.html

Small Business Entrepreneur 2003

Pacita U. Juan

Figaro Coffee, Inc.

Pacita Juan’s willingness to take risks, coupled with her passion for coffee, led her to create Figaro. Together with friends, Juan opened the first Figaro coffee shop in 1993 before Starbucks and Seattle’s Best were introduced to the country. Figaro is now the second largest coffee shop chain in the country, grabbing 30% market share. It is, in fact often mistaken for a foreign brand. From its first store in Makati, Figaro now has more than 30 in the Metro Manila and an outlet in Hong Kong. Juan is now keen on settling up shops in Vietnam, Singapore and China.

While growing the business, CEO Juan saw firsthand the dismal state of local coffee planters. She felt strongly that something had to be done to improve the situation. Through the Figaro foundation, she invites her employees and customers to contribute time, effort and resources to projects that support the local coffee industry such as the Save the Barako tree-planting activities and the Adopt-a-Coffee-Farm project.

Through Adopt-a-Coffee-Farm, Figaro taps idle or underutilized farmlands for the cultivation of coffee beans, which the company buys for its coffee blends. The project was first implemented in Amadeo, Cavite and is now being undertaken in some of the remotest and most depressed areas in Mindanao.

Juan also co0chairs the National Coffee Development Board – a government organization composed of coffee retailers, traders, farmers, rosters and other coffee experts from the agricultural, business and academic sectors. In 2003, Entrepreneur Magazine named her as one of the top 10 entrepreneurs in the Philippines.

http://www.eoyphils.com/winners03.html

Philippines Coffee Annual 2004

Approved by:

Prepared by:

![]()

Report Highlights:

![]()

Production

The country’s coffee production is forecast to decline by nearly 5 percent in Market Year 2003-04, according to preliminary estimates submitted by the National Coffee Development Board (NCDB), mostly as a result of poor coffee yield and the senility of coffee trees. Despite an increase in coffee bean buying prices for 2003 (see CONSUMPTION), increases in production may not likely be realized in the short term due to the long gestation period for coffee trees.

Despite the technical assistance and credit facilities reportedly made available by the Philippine Department of Agriculture (DA) to the coffee industry last year, production is likely to fall to 690,000 (60 kg) bags in MY 2003-04 from 730,000 bags produced last year. In 2003, the Quedan and Rural Credit Guarantee Corporation (QUEDANCOR) under the DA, made available P300 million ($5.5 million) for the rehabilitation and expansion of coffee farms around the country. According to experts, given the long coffee gestation time, it may take at least 3 years before increases in production are realized.

Local coffee manufacturers believe that government- and industry-led programs to rehabilitate the declining coffee industry are unlikely to have much impact on the industry as a whole due to the limited funding.

According to the Philippine Bureau of Agricultural Statistics, the total area planted to coffee is forecast to remain flat. The DA recently reported that

| COFFEE PRODUCTION, 2003 (In Hectares) | |

| Region | Area[1] |

| CAR | 7,628 |

| Ilocos | 112 |

| | 3,646 |

| | 1,643 |

| Southern Tagalog | 16,766 |

| MIMAROPA | 957 |

| Bicol | 1,019 |

| | 10,108 |

| | 1,647 |

| | 406 |

| | 1,657 |

| | 13,315 |

| | 29,959 |

| Socksargen | 24,495 |

| ARMM | 13,595 |

| CARAGA | 4,837 |

| TOTAL | 131,790 |

Source: Philippine Bureau of Agricultural Statistics

The urbanization and changing land use pattern in the Southern Tagalog region, notably the conversion of coffee areas to housing subdivisions and golf courses, is the main cause of this shift in production to

Consumption

The 2003 Philippine Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 4.5 percent over 2002. The recent growth in GDP is largely due to increased remittances of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW). Net Factor Income from Abroad (NFIA) grew by a robust 18.9 percent last year, despite a decline in stock of OFWs. Compensation inflow increased by 6.9 percent due to the deteriorating dollar-peso conversion. Economists predict that economic growth in the

The consumption of coffee is expected to rise with the improvement in the Philippine economy. Coffee is a common beverage for Filipinos from adults down to children. The population growth rate in the

Domestic buying prices for Robusta coffee beans, as reported by the International Coffee Organization Certifying Agency (ICOCA), increased by nearly 36 percent in 2003. The increase in domestic coffee buying prices comes after the reported decrease in production in

| DOMESTIC BUYING PRICES Robusta, 2002-2004 (Pesos/kg) | |||

| | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

| Jan | 25.50 | 43.38 | 40.50 |

| Feb | 25.50 | 43.38 | 42.50 |

| Mar | 25.50 | 40.50 | 42.00 |

| Apr | 26.90 | 39.50 | |

| May | 27.50 | 39.75 | |

| Jun | 27.50 | 35.53 | |

| Jul | 27.50 | 34.25 | |

| Aug | 27.50 | 40.50 | |

| Sep | 30.00 | 43.00 | |

| Oct | 34.68 | 42.52 | |

| Nov | 35.50 | 39.60 | |

| Dec | 40.50 | 39.00 | |

| Average | 29.51 | 40.08 | 41.66 |

Source: International Coffee Organization Certifying Agency

According to National Coffee Development Board (NCDB), the

According to Euromonitor, for the past five years, Filipinos have witnessed a robust growth in specialty coffee shops in the country, such as Starbucks and Seattle’s Best. Many believe that these coffee shops are here to stay, mainly because the Philippines is a coffee growing nation and Filipinos are loyal coffee drinkers. Local upscale coffeeshops, as well, are springing up such as Coffee Experience and Coffee California.

Trade

Coffee varieties from

In MY 2003, about 86 percent of total coffee import requirements were sourced from

Coffee exports increased slightly in MY 2003, with the majority of the coffee purchased by the Sultanate of Oman. Coffee exports are forecast to increase again next year.

Policy

In the original Philippine WTO Accession commitments, in-quota and out-of-quota tariff rates for coffee beans were to be equalized at 30 percent in 2004. However, as a result of the GRP’s 2003 comprehensive tariff review, Executive Order No. 264 was issued in December 2003 by the Office of the Philippine President, which maintained out-of-quota tariff rates at the 2003 level of 40 percent and raised in-quota tariffs for all roasted coffee beans and decaffeinated green beans. Moreover, the Common Effective Preferential Tariff Program (CEPT) under the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) grants preferential treatment for coffee from selected ASEAN countries, effective 2004.

The 2004 MFN and CEPT tariff rates for coffee are as follows:

| Tariff Code | Description | MFN | CEPT | Remarks[2] |

| 09.01 | Coffee, whether or not roasted or | | | |

| | decaffeinated coffee husks and skins; coffee | | | |

| | Substitutes containing coffee in any proportion | | | |

| | - Coffee, not roasted | | | |

| 0901.11 | -- Not decaffeinated | | | |

| 0901.11.10 | --- Arabica WIB or Robusta OIB | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 30 | 5 | Only for ID, LA & VN |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Only for ID, LA & VN |

| 0901.11.90 | --- Other | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 30 | 5 | Only for ID, LA & VN |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Only for ID, LA & VN |

| 0901.12 | -- Decaffeinated | | | |

| 0901.12.10 | --- Arabica WIB or Robusta OIB | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| 0901.12.90 | --- Other: | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | - Coffee, roasted | | | |

| 0901.21 | -- Not decaffeinated | | | |

| 0901.21.10 | --- Unground | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| 0901.21.20 | --- Ground | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| 0901.22 | -- Decaffeinated | | | |

| 0901.22.10 | --- Unground | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| 0901.22.20 | --- Ground | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| 0901.90.00 | - Other | | | |

| | A. In-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

| | B. Out-of-Quota | 40 | 5 | Except BN,KH,MM & TH |

Source: Tariff and Customs Code of the Philippines 2004

Marketing

Food Processing Sector: Key players in the food processing sector include Nestle Philippines (Nescafe); Commonwealth Food (Café Puro); General Milling Corp. (Kaffe de Oro); Universal Robina (Great Taste and Blend 45); and recently, Kraft Philippines (Maxwell House). Nestle has long dominated the coffee industry in the country and is estimated to enjoy about 85 to 90 percent share of the processed coffee market.

In 2001, to further generate economies of scale, Nestle consolidated all its Nescafe production in the city of

Retail Sector: Instant coffee has proven successful in the

Food Service Sector: The largest domestic coffeeshop, Figaro Coffee Company currently has 30 outlets, mainly in Metro Manila. With one overseas outlet in Hongkong, Figaro is now planning to open up stores in

Starbucks, the first international coffee chain to penetrate the Philippine market, has had a powerful impact on the country’s coffee drinking habits. Through it local licensee, Rustan’s Coffee Corporation, Starbucks now operates about 55 outlets throughout the country.

Following the strong entry into the market by Starbucks, numerous local and international players have also entered the market this year. Two U.S.-based specialty coffeeshops, Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf and Gloria Jean’s Coffee have just opened in Metro Manila. McDonald’s Corporation also joined the coffee retail business by launching McCafe in

| PSD Table | | | | | | |

| Country | | | | | | |

| Commodity | Coffee, Green | | | (1000 HA) (MILLION TREES) (1000 60 KG BAGS) | ||

| | Revised | 2002 | Estimate | 2003 | Forecast | 2004 |

| | Old | New | Old | New | Old | New] |

| Market Year Begin | | 07/2002 | | 07/2003 | | 07/2004 |

| Area Planted | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 0 | 135 |

| Area Harvested | 113 | 113 | 113 | 113 | 0 | 113 |

| Bearing Trees | 95 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 0 | 95 |

| Non-Bearing Trees | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 15 |

| TOTAL Tree Population | 110 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 0 | 110 |

| Beginning Stocks | 215 | 215 | 227 | 227 | 231 | 209 |

| Arabica Production | 38 | 38 | 42 | 35 | 0 | 30 |

| Robusta Production | 660 | 660 | 660 | 630 | 0 | 630 |

| Other Production | 28 | 28 | 30 | 25 | 0 | 30 |

| TOTAL Production | 726 | 726 | 732 | 690 | 0 | 690 |

| Bean Imports | 200 | 200 | 205 | 225 | 0 | 235 |

| Roast & Ground Imports | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Soluble Imports | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 90 |

| TOTAL Imports | 292 | 292 | 298 | 318 | 0 | 328 |

| TOTAL SUPPLY | 1233 | 1233 | 1257 | 1235 | 231 | 1227 |

| Bean Exports | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Roast & Ground Exports | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Soluble Exports | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| TOTAL Exports | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Rst,Ground Dom. Consum | 90 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 110 |

| Soluble Dom. Consum. | 910 | 910 | 920 | 920 | 0 | 930 |

| TOTAL Dom. Consumption | 1000 | 1000 | 1020 | 1020 | 0 | 1040 |

| Ending Stocks | 227 | 227 | 231 | 209 | 0 | 181 |

| TOTAL DISTRIBUTION | 1233 | 1233 | 1257 | 1235 | 0 | 1227 |